Featured Book Review - By Carlos C. Campbell

When Black Men Encounter Men in Blue.

©2015, All Rights Reserved.

Blue defines a color that transcends the uniforms worn by most police officers. Blue defines a culture of mutual respect, support, loyalty and camaraderie that molds this unique “brotherhood” and in recent years, a “sisterhood.” When one of their own is slain, hundreds and sometimes thousands of fellow officers, travel from throughout the United States and Canada to pay respect to the fallen. Yet within this culture of courageous public servants, there are those that abuse the public trust and dishonor their uniform. When Black men encounter men in Blue, the occasion can result in fear, contempt, disrespect, and or defiance.

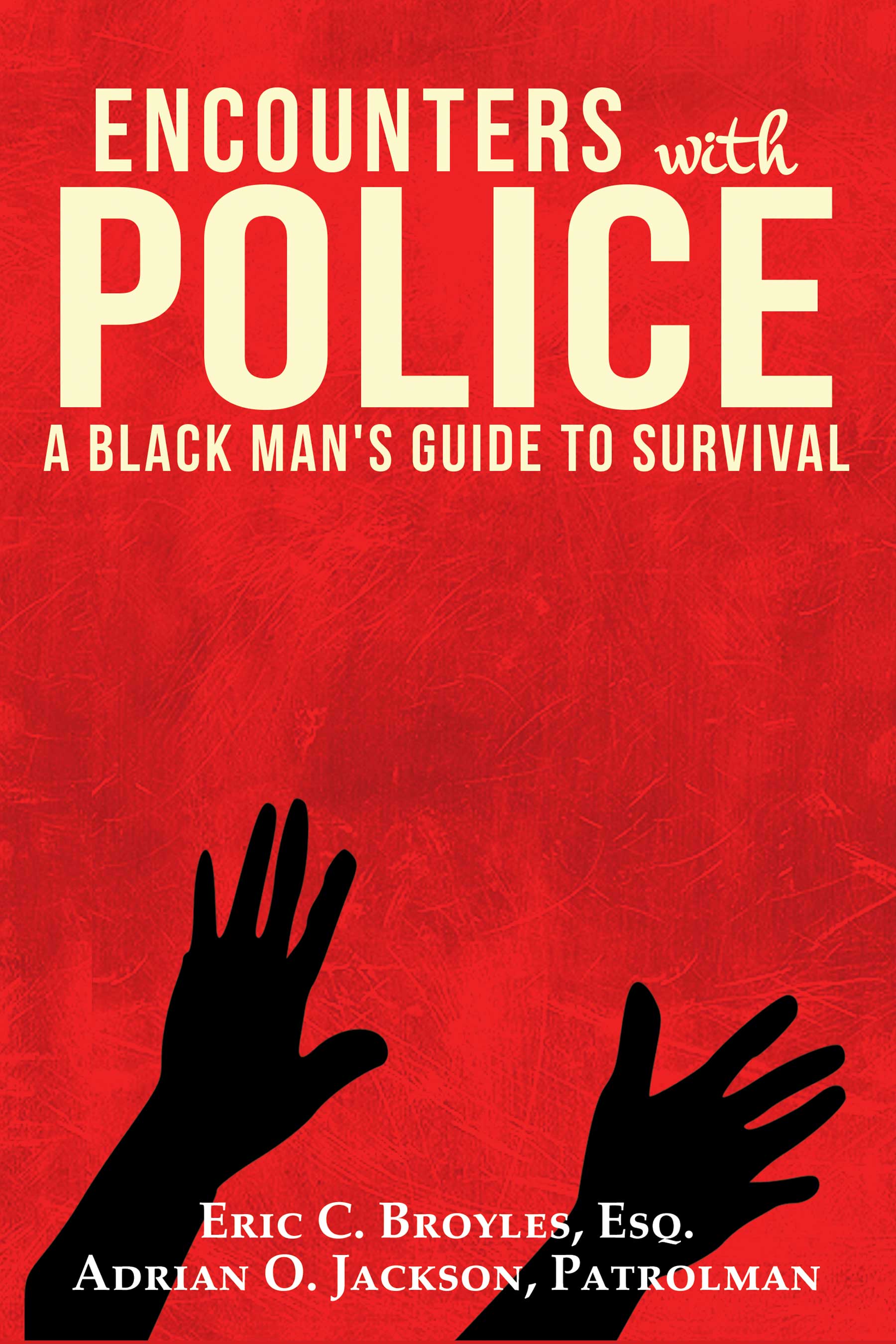

Encounters with Police; A Black Man’s Guide to Survival by Eric C. Broyles, Esq. and Adrian O. Jackson, a Patrolman, is a recently published book that warrants serious attention. This subject is one that I have dealt with all of my adult life. I wrote this review within the context of my experience to underscore its significance.

Forty-four years ago, on February 28, 1971, I penned a letter to the Editor of the Washington Post in support of the continuance of the Urban Law Institute that operated under the aegis of George Washington University. The Urban Law Institute was structured to provide training and assistance to address the pernicious assault on blacks, ethnic minorities and impoverished residents of the District of Columbia. Then as is the case now, there was and is a wide disparity in the arrest, conviction, and incarceration of individuals based on ethnicity that was unfavorably biased against black people.

The schism between black folk and law enforcement is nothing new. There is a sordid history between blacks, particularly young men, and law enforcement. This history includes Sheriff Jim Clark of the 1965 Selma, Alabama Edmond Pettis Bridge Voting Rights march and Bull Conner, one of the most nefarious characters responsible for law enforcement in Alabama. He failed to protect “Freedom Riders” from the Klan and obstructed the process of desegregating public facilities in the early sixties.

The parochial interests of white supremacists, was often in conflict with the public safety of black citizens. Police officers have been used as a foil of fear to keep black folk in line with social “traditions” and to preserve white supremacy. This practice, while widespread was not uniform.

In New York City, the Police Athletic League, sponsored track and field and baseball programs. It was the PAL in 1950 that gave me an opportunity to participate in sports. I gained a very favorable impression of police officers.

As an actor, I have declined roles that I thought were demeaning. When Director David Lowell Rich, after a successful audition, offered me the part of heading the SWAT team in Airport’79 I gladly accepted. In 1995 I again played a role as a police officer in the NBC “Homicide” series. I respect the uniform and role of a police officer.

In early January 2015, I was asked to appear on a national radio show to discuss my encounters with the police. I could vividly recall every experience, ten to be precise, with the police. Some were traumatic, like the time I was in San Francisco, CA with an architect colleague. Minutes after giving a speech at the Jack Tar Hotel, we were stopped by three unmarked cars. Blinding floodlights, lit us up in the dark of night, weapons were fixed on our bodies as we stood with raised arms outside of our car. I yelled at the top of my voice: “I’m a Fed, I’m a Fed.” I slowly pulled my ID from my coat with two fingers. The lights went off and the weapons were holstered. I was furious and used profanity to express my rage. I also let them know that I had a meeting the following morning with Mayor Alioto’s Assistant.

In September 1982, I was stopped by a police officer, about 3:00 AM, in Arlington, Virginia. I was not speeding. The police officer wanted to know where I was going. I told him that I was going to my office to work on testimony to give to a Congressional Sub-Committee. I then told him that I was a member of President Reagan’s Sub-Cabinet and that I had just returned from serving as his Envoy to the State Funeral of King Sobhuza II, in Swaziland, Africa. The officer did not have an explanation for stopping me. He seemed shocked by my response. I took his badge number and drove to my office.

When I was stationed at Alameda Naval Air Station in 1963, I was stopped by a police officer while speeding. He walked over to my 1957 MGA convertible, noticed the blue and white sticker that indicated that I was an officer and said: “We do not give tickets to Naval Officers; just slow down and take it easy.”

In the spring of 1965, I was stopped by the Fairfax County police while jogging at the crack of dawn along the George Washington Memorial Parkway. The officer said: “A woman called in and said there was a burglar in the area. To this I responded: I am Lieutenant Campbell, I live at 7736 Tauxemont Road and I am stationed at the Defense Intelligence Agency. If I see a burglar I will let you know.” This practice went on sporadically for months.

In 1977, I was driving my white Mercedes-Benz sedan, with Virginia plates, north from La Jolla, California to Los Angeles. A Highway Patrolman directed me to pull over down the off ramp. He said I was tailing (during gridlock). He asked me what I was doing in California; how long I had been in the State and when was I going back to Virginia? I said: “I had planned to leave next week but if you let me go, I can go back tonight!”

The traumatic encounters with the police can often result in eidetic images. I can recall every time stopped by Police Officers since 1954. No matter what our position is, as black men, we are targeted and must be prepared to survive. Survival depends on awareness, understanding your rights, keeping your cool and respect. If I had read Encounters with Police I would have contained my rage in all instances no matter how wrong I thought the police were. We recognize, that there is no justice without power, no power without recourse, and no recourse without relationships.

Encounters with POLICE is a must read, especially for black men and their families. Underscore the word “Survival,” because absorbing the substance of this book may save your life and or reduce your vulnerability to abuse or injustice.

Context matters. Consequently, it is essential that readers of Encounters with Police also read The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the age of Colorblindness, 2010, The New Press, New York City, NY, by Michelle Alexander, a Civil Rights Litigator and Scholar and Invisible Punishment: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment, Edited by Marc Mauer and Mada Chesney-Lind, 2002, The New Press, New York City, NY.

In 2014, Ferguson became a metaphor for the abuse of police power based on the sole criterion of ethnicity. In subsequent incidents of encounters between unarmed black men and the men in Blue, the names of Michael Brown and Eric Garner galvanized people from around the world. “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” and “Black Lives Matter,” became rallying cries following the killing of unarmed black man, Michael Brown, by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

Attorney General Eric Holder on March 4, 2015 released the report on The Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, US Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. Mr. Holder is to be commended for, in essence, chartering new ground, compared to his predecessors. This report disclosed a pattern of racial bias, and with a 67 percent African-American population, 93 percent of all arrest between 2012 and 2014, were African-American. In addition law enforcement exploited blacks to generate While the revelations disclosed in the report may shock the public throughout the entire nation, I cannot imagine any black folk with an IQ above room temperature being surprised.

We, as a people, have been awakened from a deep slumber of nihilistic disengagement. As racist and abusive that some police officers are, it is up to us to examine our culture and our domestic relationships. An FBI report indicated that the number one predictor of criminal behavior is the absence of a male in the household and this transcends income and ethnicity. We are compelled to assess the relationships between fathers in or outside of the household, the relationships between young black men that are attracted to the culture of gangs, the relationship between mothers that coddle their sons and the values that cause high rates of black high school drop outs and those that seek instant gratification.

Mutual respect is the currency for survival. As challenging as it might be, it is the best interest of black men at any age, to treat police officers with respect and to comply with their orders. The place to argue your case is in court or before a police review board.

After you read and heed the advice described in Encounters with Police, it is imperative that readers keep in mind that a negative experience with an abusive law enforcement officer, can position a person on a pathway toward perpetual persecution. The mass incarceration of ethnic Americans of African and Latino ancestry is not accidental and is the infusion of drugs and the proliferation of gangs in our major metropolitan areas.

The assault on black men is pandemic. Dystopian neighborhoods within the United States are expanding. (The Portland, Oregon based City Observatory, recently reported that in 1970, 28 percent of the urban poor lived in neighborhoods with poverty rates of 30 percent or more and by 2010, these same neighborhoods had poverty rates in excess of 39 percent.) This condition can result in the isolation, manipulation, exploitation and disproportionate incarceration of men based on ethnicity. The courageous leadership and candid assessment by Attorney General Holder, turns a new page in judicial investigations and transparency.

Harry Belafonte, singer, actor and activist for justice and social change was one of the most courageous leaders of the 20th Century. After he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in November 2014, he cited Paul Robeson who said: “Artists are the Gatekeepers of Truth. They are Civilizations radical voice.”

When Billie Holiday (1915 to 1959) sang “Strange Fruit” about the horrors of lynching in 1939, according to jazz writer Leonard Feather, the song was “the first significant protest in words and music and the first unmuted cry against racism.” Another writer, George Sinclair, credited Billie Holiday with helping to awaken the realities of racial prejudice and the ameliorative power of art.”

Throughout the sixties and seventies, other artists performed songs that were enlightening, sobering and inspiring. Sam Cooke sang: “A Change is Gonna Come.” Nina Simone sang: “Mississippi Goddam.” The Roots sang: “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn me Round.” Aretha Franklin sang: “Respect.” Peter, Paul and Mary sang: “If I had a Hammer.” Pete Seeger sang: “We Shall Overcome.” And Mavis Staples sang: “We Shall Not be Moved.”

And Marvin Gaye sang: “What’s going on?”

Martin Luther King, Jr., was right when he said: “Injustice anywhere is injustice everywhere,” and “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Carlos C. Campbell

Loseagle at aol dot com